Throughout history, the art world has often celebrated the works of men, leaving many groundbreaking female artists in the shadows. Despite their significant contributions, women have frequently been underrepresented in galleries, textbooks, and critical discourse. Yet many of these women were not just participants in the artistic evolution of their times—they were pioneers, experimenting with form, color, concept, and technique long before their male contemporaries received acclaim for similar innovations.

The 20th century witnessed a gradual shift in how women were perceived in the world of fine art, but this recognition came slowly and unevenly. Women artists pushed boundaries, broke norms, and expanded the definitions of visual expression, yet they rarely received the attention they deserved during their lifetimes. Today, a growing number of curators, collectors, and scholars are revisiting these overlooked figures, giving them the credit long denied.

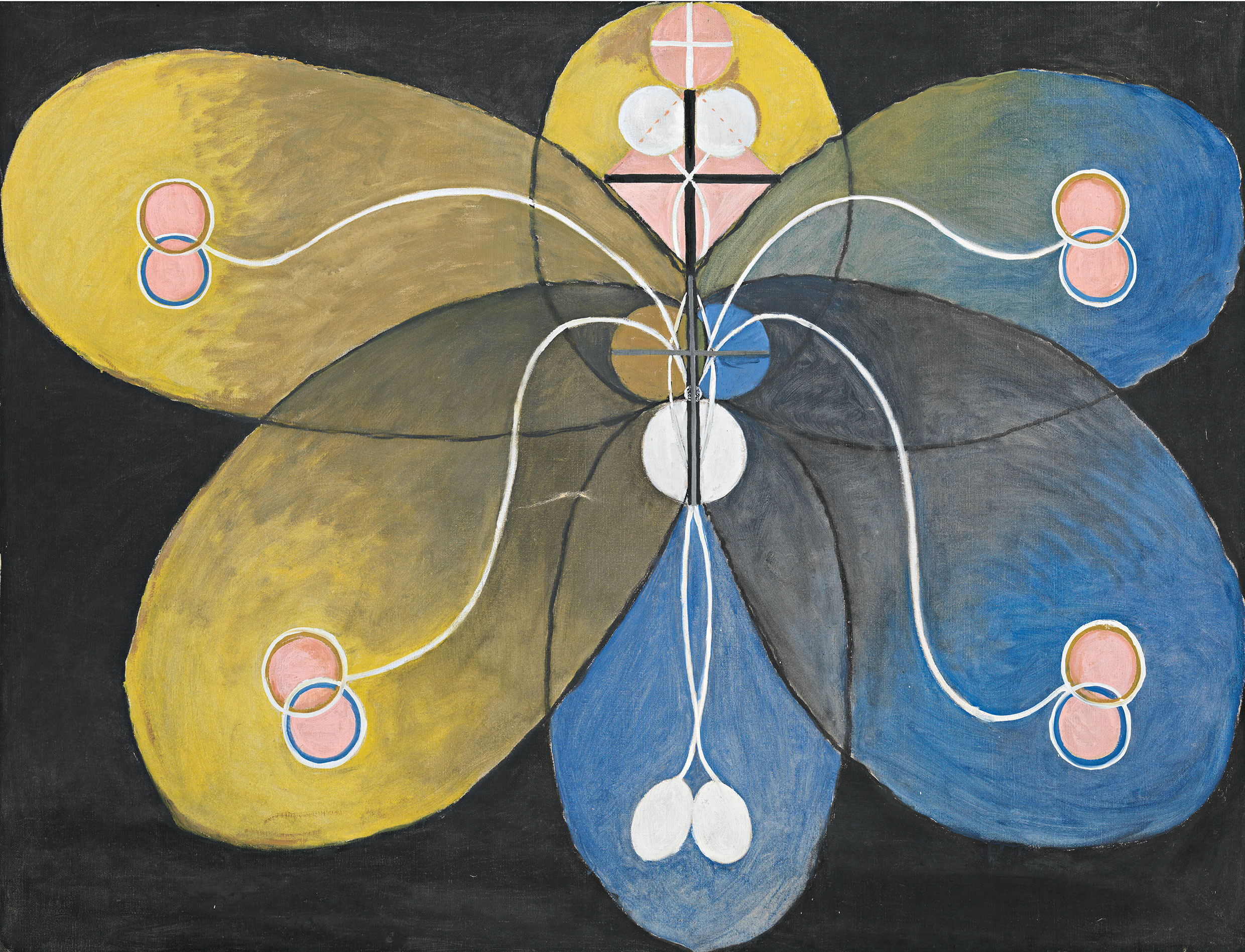

Think of Hilma af Klint, a Swedish artist whose abstract pieces came before those of Kandinsky and Mondrian by several years. Her expansive, brightly hued paintings featured spiritual and philosophical symbols, paving the way for non-figurative art that would not be recognized until many years later. Af Klint’s artworks, produced in seclusion and kept secret for years as per her wishes, are now seen as essential in analyzing the origins of abstraction.

Similarly, American artist Alice Neel defied the cool detachment of mid-century modernism by embracing raw, emotional portraiture. At a time when abstract expressionism dominated the New York art scene, Neel remained committed to figurative painting. Her works captured the psyche of her subjects, often portraying political activists, artists, and everyday people in ways that highlighted both their individuality and shared humanity. Only in the later years of her life did her work begin to garner the recognition it so clearly merited.

Another overlooked innovator was Japanese-American sculptor Ruth Asawa, who created intricate wire sculptures that blurred the line between craft and fine art. Her delicate forms floated in space, casting mesmerizing shadows and offering a new language of movement and structure. Despite her accomplishments and involvement in civic arts education, Asawa’s contributions were marginalized for years, dismissed in part because of the medium she chose and the gendered perceptions of domestic artistry.

In Latin America, artists such as Lygia Clark and Mira Schendel emerged as critical voices within the avant-garde. Clark’s interactive, participatory works redefined the relationship between artist and audience, while Schendel’s exploration of language, material, and form challenged the limits of visual representation. Both artists were central to the intellectual and artistic movements in Brazil during the mid-20th century, yet international recognition only followed long after their deaths.

Artists such as Lee Krasner, who was often eclipsed by her spouse Jackson Pollock, deserve renewed recognition. Krasner possessed a remarkable skill set, characterized by her disciplined technique in composition and daring, expressive brushstrokes, which significantly impacted abstract expressionism. Her creations not only existed apart from Pollock’s influence but also advanced in intricate and profoundly individual ways as the years passed.

It’s essential to understand that many of these women were not merely adding to existing traditions—they were forging new paths. Their innovations arose from distinct lived experiences and often reflected broader societal struggles, including issues of gender, identity, displacement, and inequality. The marginalization they faced was not only institutional but cultural, embedded in the way art was taught, exhibited, and critiqued.

The resurgence of interest in these women artists is not just a matter of historical justice. It reshapes our understanding of art history itself. When we reevaluate the canon to include these figures, we recognize that the evolution of modern and contemporary art was far more diverse and dynamic than previously acknowledged.

Museums and galleries have a critical role to play in this recalibration. In recent years, there have been increased efforts to highlight the works of underrecognized women through retrospectives, acquisitions, and re-curated permanent collections. Yet, systemic change remains slow. A 2022 report revealed that less than 15% of works in major museum collections in the United States were by women artists—a figure that illustrates how much ground still needs to be covered.

Educational institutions also bear responsibility. Art history curricula must move beyond token inclusion to fully integrate the contributions of women as central to the narrative of artistic development. This includes addressing the intersectionality of race, class, and geography that further complicates the experiences of many women artists.

Art markets, too, are beginning to correct past oversights. Works by previously underappreciated women have begun fetching record prices at auctions, and younger collectors are increasingly seeking out pieces by female artists. While financial recognition alone cannot undo decades of neglect, it does play a role in reshaping perceptions and elevating the visibility of these artists.

Importantly, the current generation of creators keeps finding inspiration from the achievements of these pioneers. Their narratives not only highlight the struggles encountered by women in artistic areas but also affirm the strength, foresight, and ability of creative expression to overcome obstacles.

In recognizing the women who were pioneers, the art community embraces a fuller and more truthful history—one that embraces all perspectives and celebrates the breakthroughs driven by bravery, defiance, and an unwavering search for artistic authenticity.